A Model for Assessing UK Societal Resilience: Analysis and Applications

The growing complexity of societal challenges has highlighted the need for robust methods to assess system-wide resilience, particularly in critical areas like healthcare and social support. This post examines a model developed to evaluate the UK’s societal resilience through the lens of societal wellbeing.

Model Structure and Design

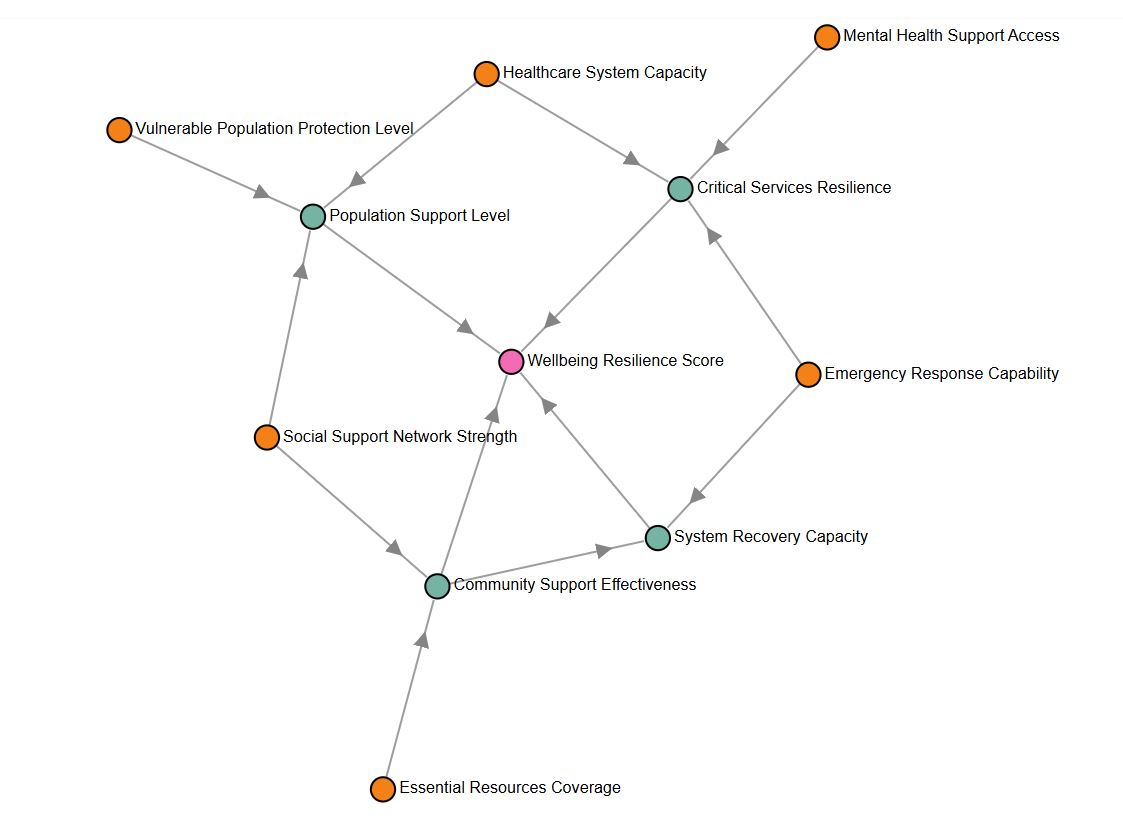

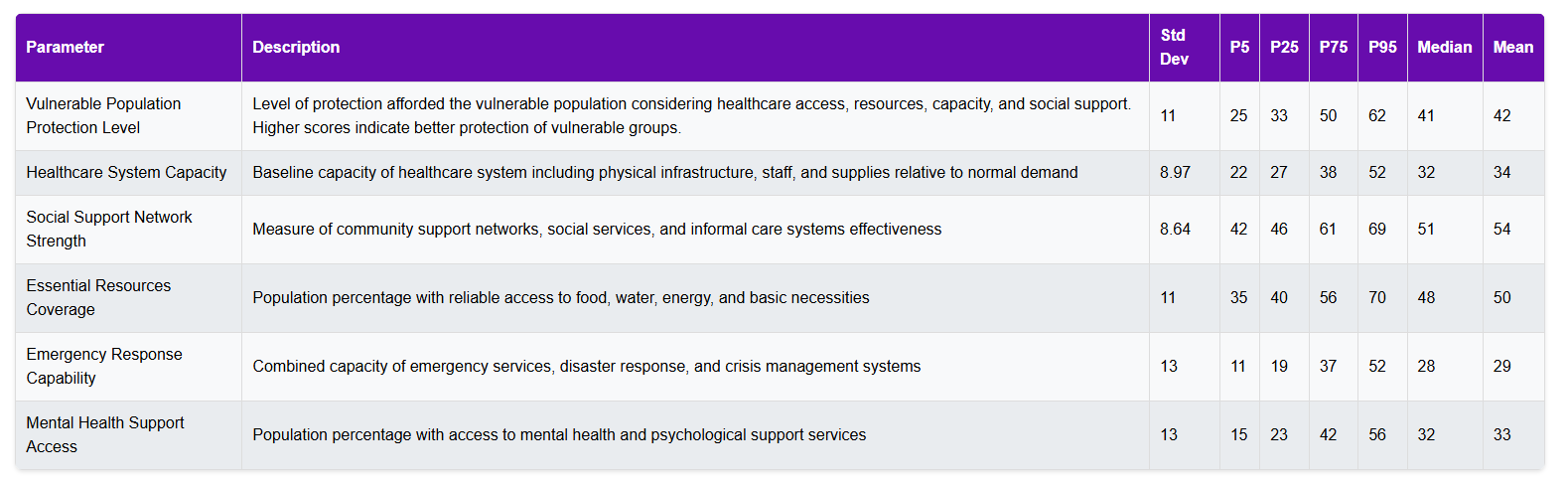

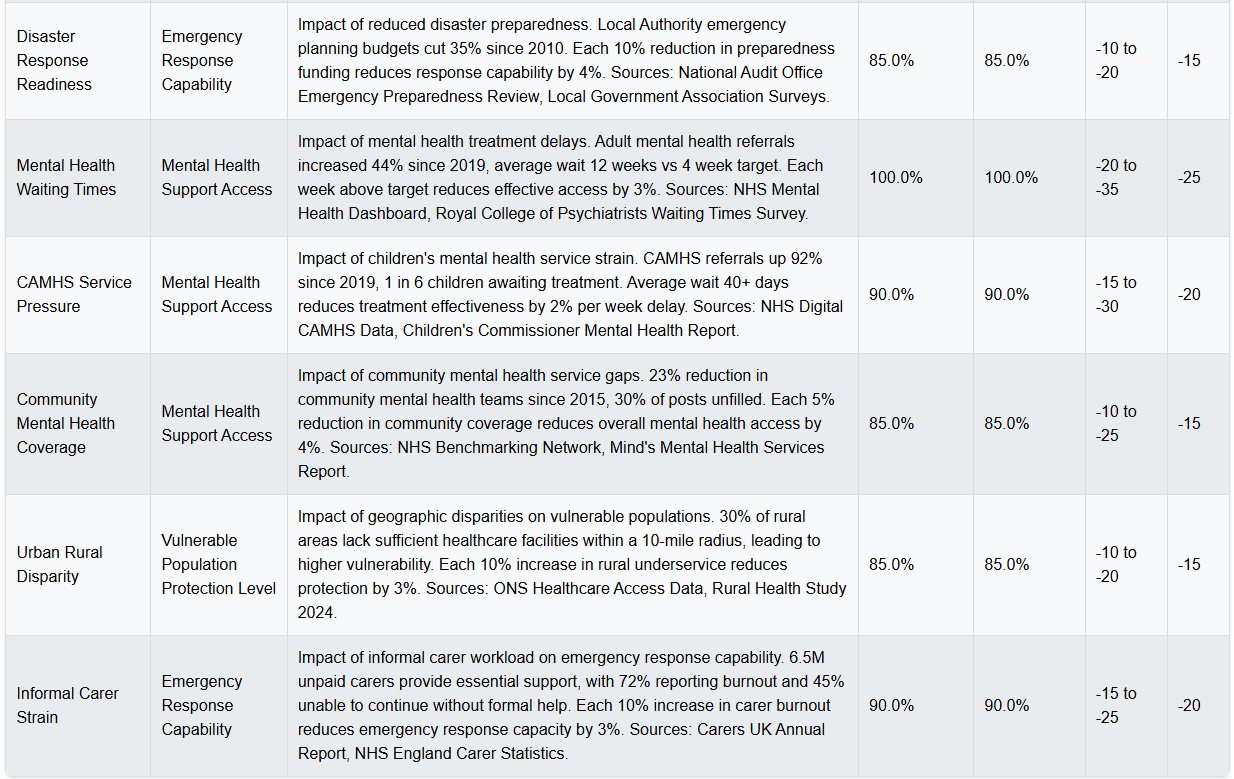

At its core, the model focuses on six fundamental parameters that underpin societal wellbeing: the proportion of vulnerable populations, healthcare system capacity, social support networks, essential resource coverage, emergency response capability, and mental health support access. Each parameter is carefully calibrated using current UK data, with base values reflecting present-day conditions.

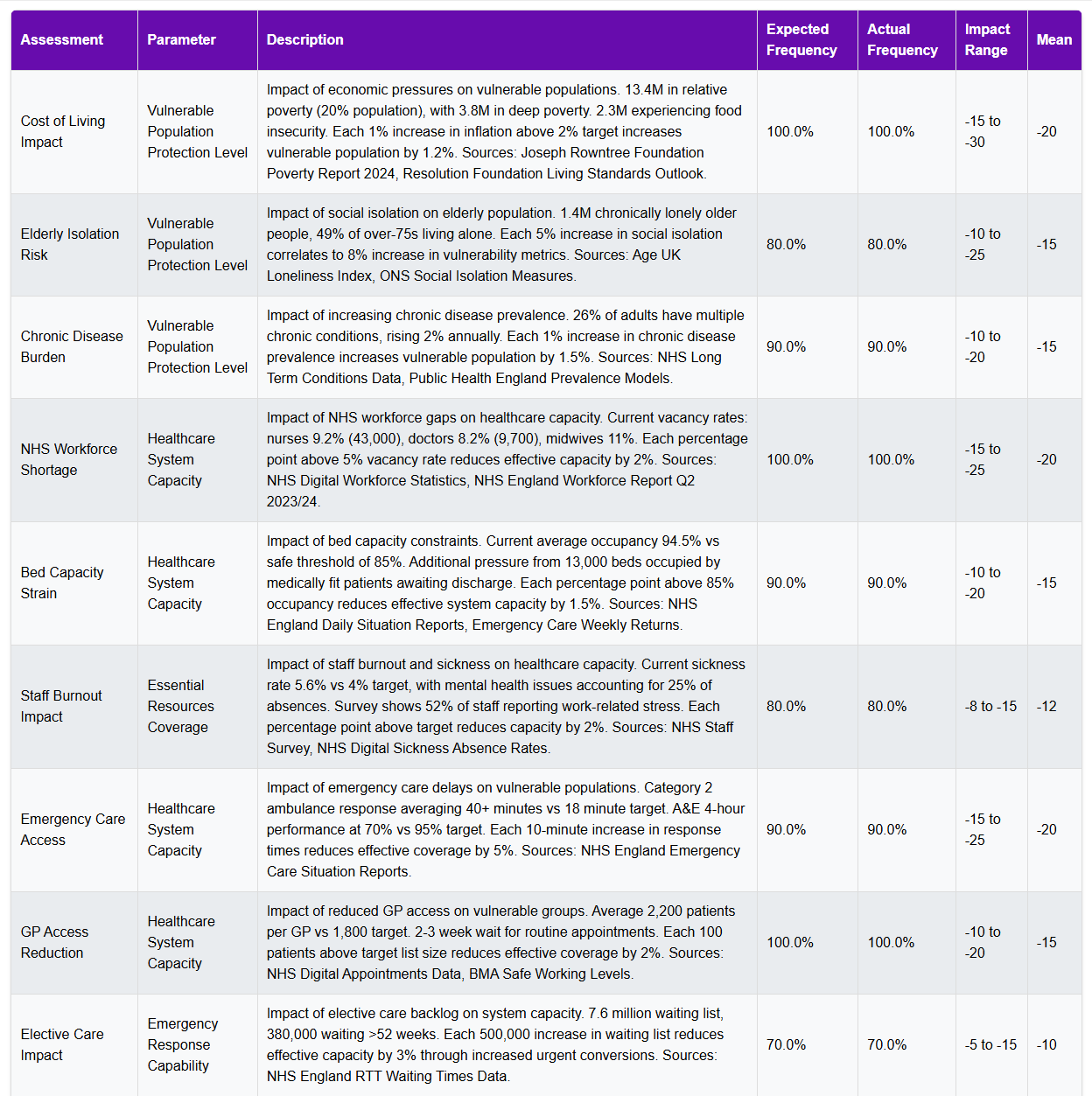

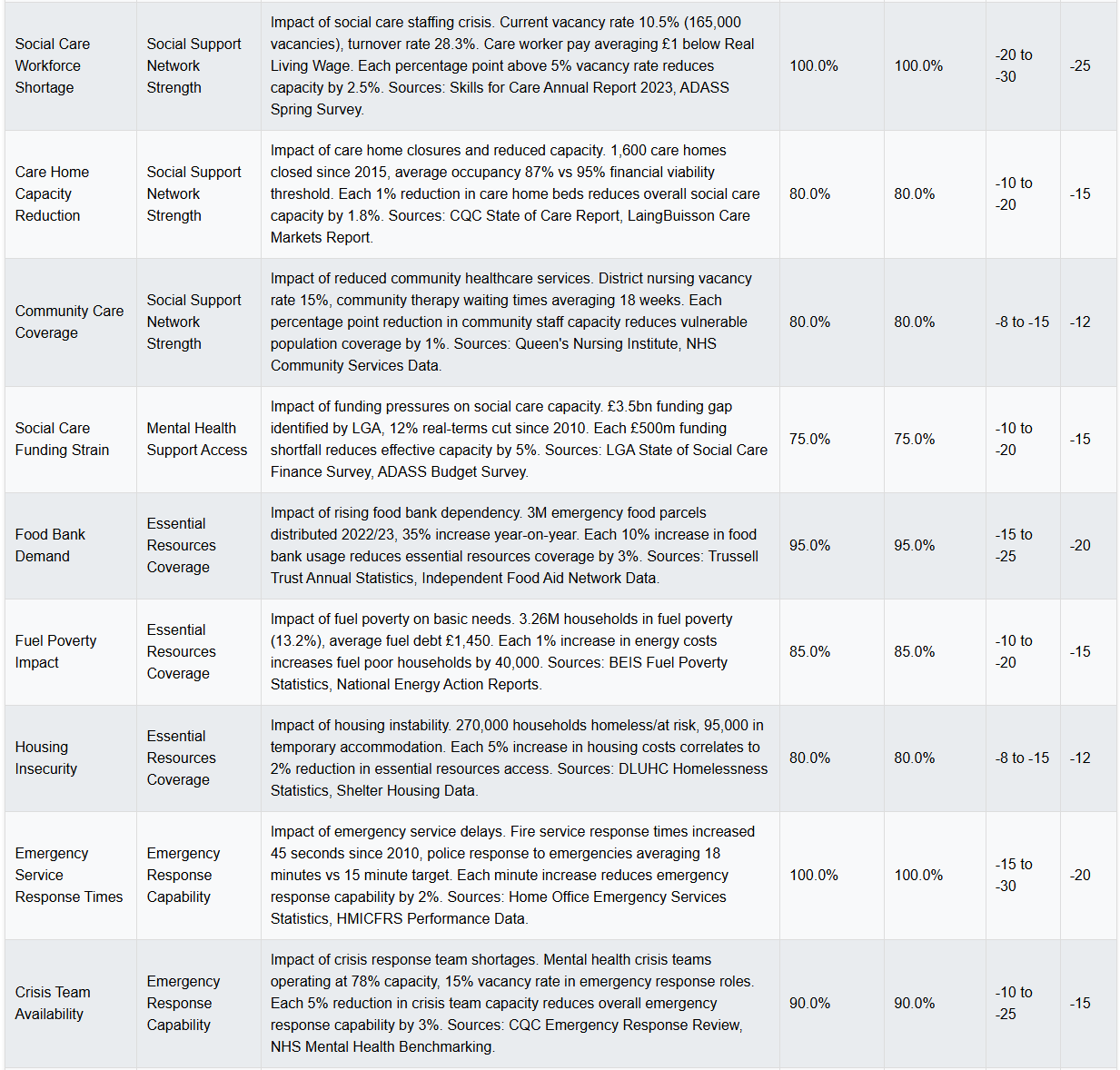

What sets this model apart is its extensive use of empirical assessments. Rather than relying on theoretical impacts, each assessment represents a documented pressure on system capacity, drawn from authoritative sources like NHS Digital, the Care Quality Commission, and public health databases. For instance, when evaluating healthcare system capacity (strain), the model incorporates specific metrics such as current vacancy rates – 9.2% for nurses, 8.2% for doctors – and translates these into quantifiable impacts on service delivery.

Strengths in Assessing UK Resilience

The model’s primary strength lies in its grounding in real-world data. By incorporating current operational metrics – like the fact that ambulance responses are averaging 40+ minutes against an 18-minute target – it provides a tangible connection between system pressures and resilience outcomes. This evidence-based approach helps validate the model’s outputs against observable conditions.

Another significant advantage is the model’s holistic approach. Rather than examining services in isolation, it captures the interconnected nature of societal support systems. For example, it recognizes how staffing pressures in social care directly impact healthcare system capacity through delayed discharges.

Purpose and Practical Applications

The model serves several practical purposes. First, it provides a structured way to understand how multiple pressures compound to affect system resilience. This is particularly valuable for policy planning, as it can demonstrate how various interventions might impact overall system stability.

For operational planning, the model could help identify critical thresholds where system pressures may lead to significant deterioration in service delivery. This capability is especially relevant for winter planning in healthcare or preparing for periods of increased demand.

The model’s Monte Carlo approach also allows for robust scenario testing, helping planners understand the range of possible outcomes under different conditions. This can be particularly valuable for stress-testing proposed interventions or assessing system vulnerability to multiple concurrent challenges.

Areas for Development

While the model provides valuable insights, several areas could benefit from further development:

The current model focuses primarily on formal support systems and could be enhanced by better capturing informal community resilience factors. This might include metrics around community cohesion, volunteer networks, or mutual aid systems.

The assessment weightings, while based on available evidence, could benefit from more detailed sensitivity analysis to understand how different weighting schemes might affect outcomes. This could help validate the model’s stability under different assumptions.

The model could be expanded to include regional variations in system capacity and vulnerability. Currently, it provides a national-level view, but local resilience often varies significantly by geography.

Looking Forward

This model represents an important step toward quantifying and understanding societal resilience. Its strength lies not in providing definitive predictions but in offering a structured framework for thinking about system interactions and vulnerabilities. By combining empirical data with system dynamics, it helps bridge the gap between abstract resilience concepts and practical planning needs.

The model’s real value may be in promoting more systematic thinking about resilience planning. Rather than treating various social challenges as isolated problems, it encourages consideration of how different pressures interact and compound. This systems-thinking approach is increasingly crucial as we face more complex and interconnected societal challenges.

For planners and policymakers, the model offers a tool for more evidence-based decision-making about resilience investments. While it shouldn’t be used in isolation, it provides a valuable complement to other planning tools and frameworks, helping ensure that resilience planning is both comprehensive and grounded in real-world conditions.

The Wellbeing Resilience Model

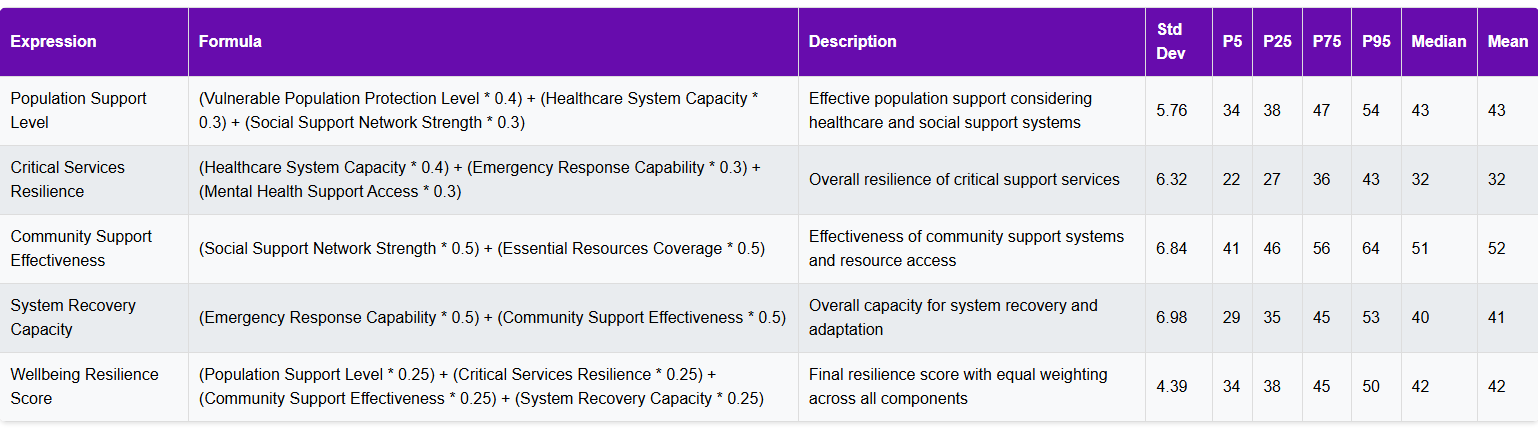

The Wellbeing Resilience Model provides a systemic overview of societal readiness, highlighting structural weaknesses and areas for improvement to safeguard vulnerable populations and critical services. It tests societal resilience by stressing core wellbeing support systems and measuring impacts on vulnerable populations, essential services, and community recovery capacity.

This model examines society’s resilience through the lens of societal wellbeing over a 1-2 year period. The model produces a Wellbeing Resilience Score from 0-100, where higher scores indicate better resilience:

90-100: Exceptional resilience – Systems are robust and adaptable

70-89: Strong resilience – Systems are functioning well with managed pressures

50-69: Moderate resilience – Systems are stable but showing strain

30-49: Weakened resilience – Systems are stressed with significant vulnerabilities

0-29: Critical vulnerability – Systems at risk of failure

The Wellbeing score combines four equally weighted dimensions (25% each):

1. Population Protection (how well vulnerable groups are supported)

2. Service Capability (healthcare and emergency response strength)

3. Community Resources (social support and essential services)

4. Recovery Capacity (ability to adapt and recover from shocks)

Each component is measured on a 0-100 scale where higher values consistently indicate better resilience. Parameters are capped at 0-100 after all assessments are applied.

Comparison with the ONS National Well-being Dashboard

Link: UK Measures of National Well-being Dashboard – Office for National Statistics

The ONS National Well-being Dashboard takes a fundamentally different approach to measuring societal wellness compared to our Monte Carlo resilience model. Where the ONS model provides a comprehensive snapshot of current well-being across multiple domains, our model specifically examines system resilience and adaptation capacity under stress.

The ONS approach uses 44 indicators across 10 domains, focusing on outcomes like reported life satisfaction, health status, and economic measures. In contrast, our model examines the underlying systems that support these outcomes. For example, while the ONS tracks the percentage of people reporting good health, our model evaluates the healthcare system’s capacity to maintain service delivery under pressure.

This difference in focus creates complementary insights. The ONS dashboard excels at tracking long-term trends in societal well-being and identifying areas of concern. Our model adds value by assessing how robust these well-being indicators might be when systems face multiple concurrent pressures – essentially testing the stability of the conditions that support current well-being levels.

A key limitation of the ONS approach is its retrospective nature – it tells us how well-being has changed but offers limited insight into system resilience. Conversely, our model’s weakness compared to the ONS dashboard is its focus on formal support systems rather than lived experience.

The ideal approach might be to use both frameworks in tandem: the ONS dashboard to monitor well-being outcomes and trends, and our resilience model to assess the robustness of the systems supporting those outcomes. This combination would provide both a clear picture of current well-being and an understanding of how vulnerable those levels might be to systemic pressures.

An area for potential development would be creating explicit links between our resilience metrics and the ONS indicators, helping to understand how changes in system resilience might impact specific well-being outcomes. This could enhance both models’ utility for policy planning and system improvement.